What it means to be disabled

Rylee Swartzel ’21 sits on her specialized wheelchair. She lost almost all of her movement after an ATV accident.

April 5, 2019

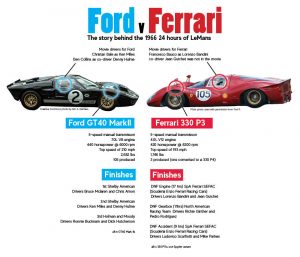

The Disabled List is a list of players who are too injured to play for a set period of time, that can be extended if the injury has not healed enough. This is common knowledge; every sports fan knows what it is. Many sports fans can tell you what players from their favorite team are on it, as well as several big-name, more famous players. But what most people never considered is what the name of the list actually meant to people. For those sports fans who grew up hearing about the Disabled List, it referred to players who were too hurt to play. But to some fans, the use of the word ‘disabled’ is not accurate.

Pressure from that particular group of fans caused the MLB to change the name of its list of injured players from the ‘Disabled List’ to the ‘Injured List’. The move was made because they felt that “disabled list” was not a fair term for players who were injured and would be playing again in their lifetime, when there were many people who were genuinely disabled for life.

This move is reasonable, and shows that the MBL recognizes that the modern interpretation of the word disabled has changed since the Disabled List was first introduced, and is accepting of change. It is a great precedent to set that change is okay, and does not need to be motivated by political correctness or a desire to please social justice movements.

Some fans think the move was overly diplomatic. They would say that the MLB used ‘disabled’ instead of ‘injured’ because it was open knowledge that the MLB intended for it to refer to players too injured to play, and that the connotation the MLB aimed for was ‘temporarily handicapped’, not ‘has a physical, diagnosed disability’.

Very few people actually voiced a problem with the MLB’s word choice. When it was introduced, it was obvious what the ‘Disabled List’ meant. Whether the meaning was offensive or not was never questioned when the popular understanding of ‘disabled’ was ‘handicapped’, and was not questioned when the popular connotation was ‘suffering from a physical disability’. Only when people spoke up recently was the name change considered, and it is still up in the air whether it was a good move or a politically correct one.

The change from ‘Disabled’ to ‘Injured’ is good. Its roots are born from a section of people who understand what being disabled truly means to those who are. It is true that in many cases, an injury is just as impactive as a disability. It is also true that in many cases, an injury serious enough can become a permanent disability. However, enough people suffer from a disability in a way different from, and in a more serious or challenging way, that a distinction between handicapped and injured has become warranted.

Take Rylee Swartzel ’21, for example. She was born without any disability. She was an excellent soccer player, good enough that she always played above her age division and colleges were already scouting her at ten years old. One day, her brother returned to her house running, telling their parents that Swartzel had flipped over while driving an ATV. She became pinned beneath it, her head pressed into mud. She went without oxygen for fifteen minutes.

She escaped with no broken bones, but the price she paid for surviving for so long without oxygen was immense; the part of her brain responsible for muscle control was badly damaged. It has been seven years, and she has not walked or talked on her own since. She can only barely move her arms, but is unable to bend her elbows; she can only just move her legs; and her hand and fingers are without motion. She can move her eyes, and her mind is still sharp, but it is impossible for her to communicate with words without the use of a board that tracks her eye movements to determine what key she wants to press.

Swartzel is an example of someone who is truly disabled. It is the extreme end, yes. Most people who are disabled are much better off than Swartzel. But she is far from the only student who is almost entirely dependent on other people.

In contrast, most injuries are temporary. A few weeks, a month in bad breaks, or a few months in the most extreme cases will see injured people back to their normal lives. Disobeying a doctor could see an injury’s recovery time increase by a few days or weeks, but that is still just time. Healing will come to all but the most severely injured.

The damage a disability will cause, though, will never fully heal. Since a disability is deeper than a simple broken bone or torn or dislocated muscle, modern science has a much harder time understanding and dealing with disabilities. Even when science can deal with a disability, its impact is always felt for the rest of someone’s life. Whether that is through clumsiness or tremors, difficulty concentrating, slower comprehension, or being unable to move in a certain way, a disability will never be fully gone.

Swartzel hopes science will allow her to walk again.

Given how advanced technology has become, it is not unreasonable – it is even likely – that a thought-based technology will allow her to live a normal life through braces or appendages that respond to her thoughts. Even if science can heal her properly, and not just through motorized appendages, she will have to relearn how to walk, how to talk, how to write, how to use the body that has been bed bound for the better part of a decade.

That is the difference between an injury and a disability. Injuries are, for lack of a better word, superficial. In most cases, life goes on as normal once the cast and braces come off. Daily routines may have to change, intense or demanding activities may have to be dropped. But with a disability, there is no ‘normal’. Most disabled people have never had ‘normal’. If they have, their disability means that they will never go back to the life they lived before it.

While modern science gives many people with disabilities realistic and practical hope, it has done far more for those with injuries than disabilities. Bones are more easily fixed than brains. Muscles are more easily rebuilt than lives. That is the difference between an injury and a disability.